Research

The search for new types of protectants

The repertoire of known desiccation protectants is limited. This reflects the fact that many desiccation-tolerant animals are not historically well-studied models with ample genetic tools for screening. Because of the great potential for desicco-protectants to stabilize biological materials, I sought an unbiased screening approach to identify strong protectants most likely to function in isolation and beyond their endogenous context. I conducted bacterial expression cloning screens with cDNA from two species of tardigrades and found that mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (mtSSBs) from each screen were among the most enriched cDNAs. These mtSSBs improve bacterial desiccation survival as well as or better than some of the best known protectants. I will continue screening for novel protectants and adapt the screening platform for yeast to capture proteins more likely to act in the context of a eukaryotic cell.

How is the desiccation response mounted in vivo?

In order to survive desiccation, animals like tardigrades and roundworms must sense a drying environment, signal across tissues, and produce protectant proteins and metabolites to promote cellular stability and survival. Our understanding of each of these steps remains limited. I am using C. elegans as a strong genetic and cell biological model system to ask and answer these questions. For example, I have shown that a late embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA-1) is upregulated during desiccation and essential for survival of osmotic stress and desiccation. An integrated organismal approach will reveal how the desiccation response is initiated and coordinated across cells and tissues in an animal.

What molecular properties underly LEA protein function?

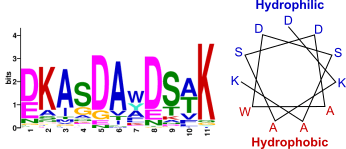

Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins are known to act as desicco-protectants in both plants and animals. Yet, the biochemical features that promote their protective capacity remain murky. I identified an 11 amino acid motif from C. elegans LEA-1 that is sufficient to improve bacterial desiccation tolerance and can substitute for the full length LEA-1 in vivo to promote stress tolerance. The conserved motif likely forms an amphipathic helix – yet this generic protein motif must contain specific functionality to promote desiccation survival. By substituting amino acids of the motif I will deduce the functional biochemical properties that confer desiccation tolerance in bacteria and in worms.

Can stress response proteins function in multiple extremes?

Different environmental stressors can elicit common sub-cellular damage. For example, protein aggregation is a hallmark of temperature stress but also occurs in drying cells. I found that small heat shock proteins (sHSPs), one of the first lines of defense against harmful protein aggregation at high temperatures, can also act to limit deleterious protein aggregation and loss of enzyme function of dried protein. How many other protectants might have cross-tolerance in limiting subcellular damage like protein aggregation or damage to nucleic acids and membranes?